DS: This DSI

is with Howard Bloom (http://www.howardbloom.net/),

a man whose career defies categorization, for he has been an entrepreneur,

entertainment mogul, social scientist, teacher, writer, and some time

philosopher. His latest book is the soon to be released The

God Problem: How A Godless Cosmos Creates. I reviewed it here,

and think it’s the best of the books of his I have read, for reasons I shall

detail, in excerpts from my review, and in questions about it. I usually open

these interviews with a round of biographical questions, but I’ll save those

for later, as well as more wide ranging questions, some queries I ask all my

interviewees, as well as touching upon his earlier works.

But, first, let me welcome him to my forum, and first allow him,

for those readers to whom his books and name are unfamiliar, to give a précis

on who Howard Bloom is: what you do, what your aims in your career are/were,

major achievements, and your general philosophy, etc.

HB:

Well I’m the author of The Lucifer Principle: A Scientific Expedition Into

The Forces Of History, which is a book that has sold between 120-140,000

copies worldwide, and some people call it their Bible—bless them, another book

called Global Brain: The Evolution Of Mass Mind From The Big Bang To The 21st

Century, and that one the office of the Secretary of Defense threw a forum

on, and brought in people from the State and Energy Departments and IBM and MIT,

and flew in a major IBM researcher from California and flew the MIT person from

Boston. The 3rd book was The Genius Of The Beast: A Radical

Re-Vision Of Capitalism and I wrote it to save Western Civilization by

giving Western Civilization a sense of what it had achieved, so it understood

what its obligation was to achieve in the future. It was originally called Reinventing

Capitalism: Putting Soul in the Machine, and showing the soul in the machine

was a vital part of that book. It won a lot of praise but I think it remains an

obscure and undiscovered book. And now I’ve written The God Problem: How A

Godless Cosmos Creates, which is probably the closest to my life quest of

these books, but they are all part of my life quest.

And what the fuck is my life quest?

“Life quest” sounds like a pompous phrase, but when I was 10 years

old, it felt like I was beaten up by everyone in Buffalo, NY, I was rejected in

every conceivable way—it felt like there was nobody who loved me in my

hometown, and that’s an understatement. But

then at 10 I discovered a couple of people who actually accepted me, people who

did not toss me out. They were Galileo and Anton van

Leeuwenhoek and I was given 2 principles by the book in which I discovered these

guys. Principle number one, the first rule of science, was

the truth of any price including the price of your life. And the book

gave the example of Galileo. And luckily, it gave the story all wrong—it told

it as myth, it said that Galileo was one of those guys who was willing to go to

the fires and die in flames if that’s what it took to advance his truth. In

reality, the pope was a friend of Galileo—they had known each other a long

time and they cut a deal and the deal was that Galileo would abjure his truth,

he would say that everything he had written was wrong, in exchange for getting

house arrest for ten years instead of being

burned at the stake, but fortunately, that is not the story I was told. The

story I was told was of a courageous Galileo who would have fought to the death

to defend his truth. Principle #2 –the 2nd rule of science-- is to

look at things right under your nose as if you’ve never seen them before, and

then proceed from there.

Look at the things that you and everyone around you take for granted.

Look at them as if you’ve never seen them before and then proceed from there.

And the book in my hands when I was ten gave the example of Anton

van Leeuwenhoek who was a draper.

In van Leeuwenhoek’s time, in order to sell cloth, you used a hi-tech

tool and that was the lens. The lens had been developed 500 years earlier for

spectacles—reading glasses. But the use of it in the way van Leeuwenhoek was

using it was relatively new. And

van Leeuwenhoek got an idea and his idea led

him to custom-grind a lens that would allow him to look at teeny-weeny

little things, not just the weave of a fabric and he started looking at

teeny-weeny little things all over the place, which led to a story that the book

didn’t tell me, and it’s a story about courage and it’s a story about

looking at things right under your nose. Van Leeuwenhoek looked at a bunch of

fluid and discovered it had little tiny animals in it—highly active little

tiny animals swimming around with whipping tales. Now what was the fluid he

examined? His own sperm. In other words, he had the courage to masturbate, which

is something that you’re just not allowed to talk abouta at all, and he had

the courage to look at his own sperm, examine it scientifically, and he made the

discovery of microorganisms, which led to all of microbiology. So those 2

rules—the truth at any price including the price of your life and look at

things right under your nose as if you’ve never seen them before—those

became my mission in life and I have been in science since I was 10. To me

it’s my religion, and I will do anything I can to deliver you the truth and I

will do anything to deliver you a truth that gets you and me both to look at

things as if we’ve never seen them before, in ways that are surprising and

stunning. And I will do anything I possibly can to tell you a story in such a

vivid manner that it’s easy to understand and that it grips you like a novel.

So that’s my life quest.

DS: As stated,

let’s get this interview started with taking on your upcoming book, The

God Problem. Before tackling what its contents are, and how you

came about its idea, let me first talk about the book’s marketing and

pre-release. Over the last couple of decades you have had a few successful

books- at least in terms of name recognition- I don’t know of sales nor the

like. Yet, despite that cachet, you took to the Kickstarter website, and this

page, to raise $20,000 (successfully) to market the work. First, why did you

feel a need to got this unconventional route? Second, did your publisher,

Prometheus Books, refuse to back its own product? And what does this campaign

allow you to do that, sans it, you would not have been able to do?

DS: Given that

you are a de facto Name Brand author, and still went this route, what does this

say to you of the future of publishing? Are too many huge advances being paid

out to writers and books that have no realistic chance of recouping their costs?

If you could reconfigure the publishing industry- at least for that area you

occupy (nonfiction, science, etc.) what would you do? Do you think that e-books

are the future? I’ve thought that it will take one author to have Harry

Potter or Twilight

or Dan Brown level

sales (albeit hopefully better literary quality) to change the current paradigm,

and then the big publishers will find themselves dinosaurs in a Wild West

environment where technology utterly rents their economic model. I’d say this

occurs no later than 2030. Any thoughts?

HB:

E-books have got to be the future—I bought my Kindle 3 and half years ago and

I do all of my reading on my Kindle, it reads stuff out loud to me through

headphones while I do exercises in the morning or walk two miles through

Prospect Park in Park Slope, Brooklyn, to the Tea Lounge, the cafe where I do my

writing. There are 265 items in my Kindle right now—that’s a library.

That’s 100 lbs of books, or 250 lbs of books and yet I carry them around with

me everywhere. When I was on the train last night coming back from a wedding in

Hudson, NY, to New York City, there were more people carrying Kindles and iPads

than I have ever seen before. When I sat down in the train

station waiting area once I got back here to New York and popped onto the

wifi to run an online meeting for an hour,

again, at first I was struck by the number of people who had iPads and

then I was struck by the number who didn’t, and what looked like a lot of

iPads were 4 in a room of 200 people. That means 196 people don’t have

them, and you know those people are going to have iPads 5 years from now. Or

they will have some form of tablet,

so they will have the option of reading books. Once upon a time, in the record

industry, in 1922, 600 radio stations were licensed.

Record companies had been making tons of money for over seventeen years.

The first record to sell millions of copies sold 5 million copies for The Victor

Company in 1905. It was a record by

Enrico Caruso. So by 1922, there was a flourishing record industry, and that

industry looked at radio and said, ‘Oh my God, this is going to put us out of

business.” Why?

Radio might mean that people would not have to pay for records.

They’d get their music for free. The

record industry panicked. It started putting these labels on its records that

said, ‘You are only permitted to play this in your own living room. If you

play it anyplace else, the FBI will be all over your back. They will punish you

severely.’’ And they said that so that there wouldn’t be free airplay

of music. But guess what the record companies discovered in the 1930s and 40s?

If you had a lot of free airplay, it increased the sales of records. And by the

1950s record companies were sending

guys into radio stations to lobby to play records on the air for free, while

offering cocaine and money and anything it took to get free airplay. Something

like that is going to happen in the publishing industry. And both books and

e-books will flourish, and in the end e-books will make paper books flourish all

the more. I’m not quite sure how, but that is what is likely to happen.

DS: That said,

what have been the major criticisms of your book and ideas, online or off, in

essay or fora, and what is your response?

HB:

I made a list of 600 people I respect, and whose books I liked, and I believe

there was only one negative response out of 100 and it came from Paul Davies.,

Paul Davies is a physicist and cosmologist and his books have been

chasing the mystery of emergence for a long time, and the mystery of emergence

is an important part in The God Problem.

Paul Davies said he wished I hadn’t attacked the 2nd Law of

Thermodynamics. He said I wish you

hadn’t have said that the concept of entropy is all wrong. And his

justification was a strange one. He said many good minds have put many years

into the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics. Now think about that—if you

think about the Second Law, it says all things tend towards disorder. All things

tend towards entropy, and the image used to illustrate the point is usually take

a sugar cube and drop it into a glass of water and wait 15 minutes or swirl the

water around. What happens? The sugar cube dissolves. Well, that’s what

happens with everything—the entropy believers say. And then they give you the

concept of heat death, which Lord Kelvin came up with in 1851, and the concept

of heat death says that eventually the universe will do what a sugar cube does

in a glass of water. It will dissolve into a formless muddle.

This is so outside the bounds of the real universe that it defies belief.

The real universe is constantly creating new forms and disgorging new

forms of organization, and whomping together new emergent properties.

The idea that everything is moving toward a muddle is ridiculous.

Frankly, in a universe of entropy, that there would be no you and me. Period. So

to say that I wish you hadn’t taken on the 2nd Law of

Thermodynamics because so many great minds have spent so much time on it is not

good science. It would be one thing

if Davies had said we should not criticize the concept of entropy because so

many great scientists have done so many experiments that have proven it right.

That’s what you’d expect to hear, the proof. But no, if I’m paraphrasing

him correctly from memory, that’s not what Paul said. What he said was simply

that a great many minds have dedicated themselves to the

concept of entropy. Well, you could say that about Buddhism,

Christianity, look at all the people who went into monasteries, who became nuns,

who went through lives of celibacy in order to be priests. You could say I wish

you hadn’t questioned the idea of God, because look at all great minds that

have dedicated their lives to it. That’s not a justification for anything.

Especially in science.

We humans leap passionately to embrace systems of belief that make sense

to us, but the fact that these belief systems make sense to so many doesn’t

mean they fit the real world, or that they’re valid lenses to see the real

world in ways that will allow us more predictive powers. And science is all

about seeing what’s under your nose, looking for the truth, and looking for

the truth that surprises. It’s about looking skeptically at

truths that are accepted by a vast mass of great minds.

It’s about looking with a fresh eye at the things that many bright

minds have taken for granted. That’s

the second law of science. Look at

things right under your nose as if you’ve never seen them before.

Look at things that you and everyone around you take for granted.

Look with a fresh eye at things even great minds have accepted as basic

truths. And in the case of the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics, looking

with a fresh eye tells me that it’s crap, it’s bullshit. It doesn’t fit

the universe of continuous creativity that we live in.

Hector Zenil of the Institut

d'Histoire et de Philosophic des Sciences et des Technique, who said The God

Problem was “thrilling” and he couldn’t stop reading it until the end,

also said he wished I hadn’t attacked the notion of entropy. So that was the

one criticism that I can remember.

DS: Also,

since science is about testing hypotheses and requiring proof, what hypotheses

of yours have met empirical proofs? And, if none have yet, when and how do you

propose to test them? And, if they fail to meet expected results, what happens

to your theory? Do you, ala the Big Bangers, create an ad hoc patchwork, or do

you scrap it all, and start afresh?

DS: Let me now

turn to The God Problem,

and given the book’s heft, and that it has been some months since I read it, I

think the best way to give folks at least a flavor of it is to tackle some of

its larger points by referring to the lengthy review

of it I did, quoting some of the passages, and letting you respond or expound

where needed. First, what is the titular God Problem?

HB:

The God Problem is this—if there is no God, then how was the cosmos created?

In Genesis it says that God spoke, that God spoke and there was the heavens and

the earth and God parted the heavens from the seas and said let there be light

and there was light, and there is light. And the fact is that there is a lot

more than just heavens and seas and light, there are protons, neutrons, planets,

stars, octopi, palm trees, and you and me.

So how the fuck did the universe create these things without a God?

That’s the God Problem.

The use of God of in the title in my case was not a marketing ploy

because, to put you back in my shoes again, look at what your mission in life

was—you were given a mission in life at the age of 12.

God knows how missions land on us. That’s another subject for another

time. But your mission was to find the Gods and to figure out what these Gods

are, and that includes a big mystery—how does a cosmos without a god create

space, time, atoms, stars, galaxies, and life. It’s all a huge mystery and

modern science is only giving us the tiniest glimpses of the answers.

DS: When you

asked me to read the book and proffer a blurb for it, I wrote this:

The God Problem is Bloom’s

best, as well the best GOD-titled, book ever. Eschewing obsessive atheistic

evangelism (Dawkins, Dennett, et al.), Bloom focuses detailed Linnaean

naturalism with Boorstinian narrative to argue for a cosmos not Intelligently

Designed, but Emergently Patterned. Bloom does not leave the universe to the

stars, but fractally connects natural design to human creativity, bridging

seemingly disparate fields as cosmology, mathematics, neuroscience, linguistics,

and the arts. The book never mentions Keats’s Negative Capability, but does

better; it enacts it.

There are several points I want to engage with. First, was the

dropping of the word God into the title purely for marketing purposes?

The reason I ask is because I do state this is the best book with that term in

it that I’ve read because so many people whore their science or life

experiences with that term: The God This, The God That….

Second, despite the use of God, the book has surprisingly

little about religion in it. You seem to assume that folks reading the book will

buy into your non-theism at the get-go. Therefore you don’t seem to bog down

into the relentless warrior mode that Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Sam

Harris types do. By doing so this allows a clarity that I find missing in their

works, plus an accessibility that their works lack: i.e.- you’re not an

evangelist. What are the pros and cons of this approach?

HB:

Well, let’s look at the negatives of Dawkins, Sam Harris, and Christopher

Hitchens. Science is about being open-minded. Everything is a tentative

hypothesis, and you have to know that a hypothesis you hug and cherish might be

disproven later and it may be your job to be the one to disprove it.

Even if you are the one who came up with it. When scientists commit

themselves to a hypothesis as an absolute truth, they don’t realize it but

they often set up a church-like

structure, and Dawkins has set up a church-like structure in which he is the

Pope and in which there are heresies and if you believe in those heresies

you’re out of the church. Well, that’s not tolerance, pluralism or science.

Dawkins is brilliant and an extraordinary communicator, his ideas are extremely

useful, his books are well worth reading, but the fact is he’s become

intolerant. He has been what St. Augustine was—another brilliant mind. And St.

Augustine took off on a heresy hunt and it made him less than human. It made him

cruel, vicious and intolerant. Well, Richard Dawkins and the crew are not

putting people to death, which is something that St. Augustine did, but it is

not science to say that something is absolutely wrong and should be wiped out of

the human vocabulary of concepts.. That is not science—that is dogma. Dogma is

not science, dogma is religion. I think I’m an evangelist, but I am an

evangelist on behalf of an open-minded science and an amazingly creative cosmos.

DS: Briefly

contrast the ideas of Intelligent Design vs. Emergent Patterns.

HB:

The fact is that Intelligent Design people think that because the cosmos exists,

there had to be an intelligent designer who created it. And it’s an

interesting idea to analyze. What do we really mean when we talk about designing

something? We mean that in the designer’s brain, 30 to 40 visual centers began

to visualize something that had never existed before and then the designer took

his vision and figured out how to instantiate it as a reality. And Intelligent

Designers believe we need a God to imagine all this stuff, and then to make sure

that it happens. Well, sorry, if you need a God to do that, who made the God?

Who designed the God? So what does the concept of Emergent Properties say about

how this astonishing cosmos came to be? The paradigm of emergence is something

that George Henry Lewes and John Stuart Mill came up with in roughly 1835 in

London, and the whole extraordinary story of these guys is in the book. In the 1830s, George Henry Lewes and John Stuart

Mill were sitting around thinking about this new thing called chemistry.

They were thinking about the fact that

oxygen and hydrogen, are

both gasses, you can pass your hand through them, you can see through them,

often you don’t even know they’re there.

If you add two bell jars of these gasses, one bell jar of oxygen and one

bell jar of hydrogen, based on the logic and the arithmetic of one plus one

equals two, one hydrogen gas plus one oxygen gas should equal two gasses.

Right? Put hydrogen and oxygen together, they’re both gases and so you

should get a gas. Gas in, gas out. Makes sense? Well, what happens if you put a

match in? All you’re adding is heat,

so you should get nothing but a slightly warmed gas. That’s simple logic.

Except that’s not how it happens. You put the hydrogen and oxygen together,

and it’s a gas. Fine. But you put

in a match, and there’s an explosion. Where in hell did an explosion come

from? That’s a radically different reality than a gas. But even more

astonishing than that, you get something else that’s radically unlike a gas. It’s a something you can feel with your fingers, but unlike

solid stuff, you can put your fingers through it. And it does strange things. It

can make a puddle on the floor. It can soak into your pants and make a stain

that embarrasses the hell out of you. It

can ball up in spheres. It’s

called liquid, it’s called water. Now if you take a really close look at

hydrogen and oxygen and and you’ve never seen this stuff before, there’s no

way in hell you can predict liquid water. If

you do a minute analysis of hydrogen and oxygen and add their qualities

together, you can’t predict an

explosion. And, you can’t predict

liquid—that’s an emergent property. When we talk about the emergence of

water, that’s an emergent property. So is the explosion. When we talk about

emergent properties, are we talking

about things that a God of the cosmos does?

Is there a God in the hydrogen and another God in the oxygen?

Have the two of them copulated? Does

a designer God need to picture an explosion and water in his head before they

can take place for the first time? If

you’re an atheist, the answer is no. Take

hydrogen, oxygen, put in the flame and wham. You get an explosion and water and

all of that happens without a God. So if that can happen without a God,

presumably a cosmos can happen without a God. That is the difference between

Intelligent Design and Emergent Patterns. We know the hydrogen and oxygen reaction is for real and that

it produces water. But we still

don’t know how and why it happens. We can’t explain it—we still can’t

explain water, the example that George Henry Lewes and John Stuart Mill were

using in 1843, nearly 170 years

ago. That was the phenomenon that

prodded George Henry Lewes to come up with this word: emergence. And we still

haven’t solved the puzzle. So Emergent Patterns happen without a God, the same

thing may have happened with the Big Bang, which could have come to be in a way

that doesn’t need a God. And the idea of a God is ridiculous because if you

need an Intelligent Designer to explain anything complex, then God is complex as

hell and we need an Intelligent Designer to design the God. And if we needed a

God to design the God then we need a God to design the God who designed the

God…it keeps going. It’s

called an “infinite regress.”

DS: Finally, I

mention the idea of poet John Keats’ Negative Capability, yet

you never use the term in your book, yet, in correspondence with me, you seemed

to have an Aha! Moment yourself, as if you unwittingly stumbled into something

with deeper implications than you realized. Is this so, and, having now realized

this connection, has this catalyzed any ideas for future works, or an expansion

of your ideas within?

HB:

I went and looked Negative Capability up on Wikipedia and I was stunned by the

concept, and in essence it’s another way

of expressing the second rule of science—look at things right under your nose

as if you’ve never seen them

before. I think the concept of Negative Capability, because it keeps escaping my

memory, is the fact of seeing something in what’s under your nose that

you’ve never seen before. Actually doing the seeing, not thinking of the

seeing. Doing the seeing that stuns you. And yes, I tried to achieve that in the

book because that is the 2nd Law of science—I have to look at

things with wonder and awe in order to question them and come up with new ways

of looking at them and I want you to see the wonder and awe in these things

because they are wonderful. They are awe-filled. The universe is filled with

things that go on right under our nose that we never see.

DS: Why did

you put autobiographical elements into your book, and do you think that, because

this necessarily removes it from a work of hard science, it does long term

damage to your larger ideas? What do you see as the tradeoff for this stylistic

conceit?

HB:

Scientists for 250 years have been trained in a certain academic form of writing

in which they make their work objective. And how do they make their work

objective? They take all their autobiographical elements out of their work.

Well, what does that do? It makes reading academic science research articles

very hard. I know, I’ve been reading journal articles and hard science books

since I was 11 years old. And sometimes in mass quantities and they’re

extremely frustrating because you don’t know why the scientists are asking the

questions they’re pursuing, you don’t know what significance of the answer

is. Why? Because the scientist has

been trained not to tell you anything about his or her life. She’s been trained not to tell you why the question and

answer means something to her. She’s

been trained not to tell you about her motivation and her thought process. I was

reading a book by Heinz Pagels in the 1990s,

I think it was

The

Dreams of Reason: The Computer and the Rise of the Sciences of Complexity. And Pagels put a biographical element in his book. The result

was amazing—all of a sudden, this bit of his personal history illuminated why

he was pursuing the topic he was pursuing—it made

his ideas meaningful. And I realized, we are being robbed of something

massive when 350 years of scientists won’t tell us the autobiographical

stories that explain why they found the questions they dedicated their lives to

so compelling and why they found the answers so useful. So I put in the

autobiographical element. And I put it in for another reason—in order to get

across an idea, you have to tell a good story. You have to tell a story that’s

gripping and that will open a door to the person reading the book and make him

or her feel not just a part of the story, but in the very center of it. And the

narrative that pulls all the questions in this book together, all the questions

I’ve tried to tackle in this book, is the autobiographical narrative. I’m

trying to give meaning by giving you the context of my life.

The sort of context that made Heinz Pagels’ writing hit home. I’m

putting you in the center of my life so you see the meaning of the questions

that I am asking.

DS: I then

quote from the book regarding the Five Heresies. What are they, why are they

important, and what relevance do they have to the book’s premise?

HB:

Heresy #1 if A = B and if B = C

then A = C. That’s the basis of

Aristotle’s logic, the logic that you and I use every day.

It’s at the heart of the logic that science uses without question or a

second glance. That cornerstone of logic is what Aristotle called his basic

syllogism. And Aristotle’s

syllogism is based on the assumption that A = A, but what if A doesn’t = A?

What if the A I just said a second ago is different from the

A I said two seconds earlier. Remember,

each A involves a different movement of molecules of air.

Each A popped out of a slightly different setting of the hundred billion

neurons in my brain. And each was

absorbed a bit differently by the hundred billion neurons of yours. What’s

more, each A was spoken at a slightly different position on an earth that moves

seventeen miles around its axis every minute, an earth that moves 556 miles

around the sun in 60 seconds, and an earth in a solar system that moves 864

miles a minute around the core of our galaxy.

No two A’s are precisely alike. Each involves a different swatch of

matter. Each takes place in a

different time. Each emerges in a

different place. Each has a

different context. And context

counts.

Heresy 2 is that 1 + 1 does not = 2. For an example, go back to what

George Henry Lewes and John Stuart Mill were looking at—put two gasses

together and you don’t just get twice as much gas. Second by second, that kind

of thing happens all over the universe and if you don’t understand it, your

math and logic will only take you a certain distance and then will leave you out

in the cold and you won’t understand you’re out in the cold because you’ll

try to make all natural phenomena fit your arithmetic and that’s not the way

it should be, you should make an arithmetic that fits the cosmos. So 1 + 1 does

not always = 2.

Heresy #3 is that the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics—that all

things fall apart, that all things tend towards disorder, that all things tend

towards entropy—is dead wrong. It does not fit this cosmos whatsoever.

In this cosmos things do not fall down, they fall up. Things do not fall

apart, they fall together. Yes, they fall apart to a certain extent, but what

falls apart always falls together, and usually in a far more creative way

than in the 1st way it fell together.

Heresy # 4 is that the idea that we live in a random universe—the idea

of the sort of randomness that’s used to explain Darwinian evolution over

and over--is wrong. This is not a

six monkeys at six typewriters

universe. This is a far more ordered and structured universe, The number of

choice points the universe has at any given moment is

fewer than those who use the mathematics of probability theory would guess.

Heresy # 5 is that information theory, which has been crucially important

over the last 50 years, is dead wrong.

In fact, one of information theory’s most basic premises is so far off

the mark it’s ridiculous.

DS: Another

tactic the book deploys is the revivification of historic figures without

falling into tired anecdotes; something practiced by the late, great historian

Daniel J. Boorstin. First, why this tack, and second, which of the anecdotes on

historic figures that the book uses was the most illuminating for you, either

personally or in regards to the God Problem?

HB:

One of the most illuminating moments for me was when you used Loren Eiseley and

Daniel Boorstin as yardsticks to measure this book.

You were dead right. Loren Eiseley moved me tremendously in the 1970s,

and I loved his way of doing science with poetry and there is a guy named Giulio

Prisco, a veteran of the European Space Agency, who has written on the website

KurzweilAI, Ray Kurzweil’s tech-news website, that this book is science

poetry. But as you pointed out, I do not reach Loren Eiseley’s heights, and I

wish that I did.

Secondly, Daniel Boorstin was an incredibly important figure in my

intellectual life because I was struggling to learn history from the age 16 on

and it wasn’t until Daniel Boorstin’s The Discoverers came out in

1983, it wasn’t until Boorstin told such vivid, riveting stories that he made

the whole pattern of history knit itself together in my mind for the 1st

time and that was a tremendous gift. When it comes to the scientists whose

stories I tell, there are huge numbers of them that I researched, and every one

of them was a revelation and an illumination because when I dove into their life

stories, I found that their life stories hadn’t been told accurately. And that

there were amazing things that we were not normally told about these people. For

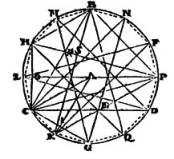

example, we imagine that Kepler came up with the 3 Laws of Planetary Motion. Ok,

I dare you. Go on Google Book search and pull up all the works of Kepler and

look for the 3 Laws of Planetary Motion and you won’t find them. One of the

reasons you won’t find them is because the 3 Laws of Planetary Motion are

mathematical and that, to us, means

the use of equations. And Kepler didn’t have equations. Yes, he had something

he called math, but it’s what we call geometry and he drew triangles inside of

circles. Sometimes as many as 40 triangles intersecting inside a circle in order

to figure out a complex problem. That was his form of mathematics. And we have

to realize that the equations we

take for granted as math, have only been math for the past 300 years, and they

are just as tentative as any other form of math or of human thinking that’s

ever existed—they’re not the be all end all of the world. That discovery was an astonishment.

DS: While I

had high praise for the book, I did not agree with all the book’s points, and

my biggest objection requires me to quote lengthily from my essay and the book:

Now, let me get to metaphor, and how I think Bloom has a problem. While I

agree that metaphor is an apt way for how we humans to approach the cosmos, I

don’t believe meaning derives from it.

Bloom details the history of why metaphoric thinking is deemed

unscientific, then counterattacks:

Light, says current physics, is simultaneously a wave and a

particle. And guess what? Though Aristotle says that “metaphorical reasoning

is unscientific,” a wave is a metaphor. So is a particle.

How did the highest of the modern sciences—physics--get the notion that

light is both a wave and a particle? From metaphors

After digressing on Leonardo da Vinci, Bloom writes:

What’s more, this battle of the metaphors would go on for

three hundred years. The battle of the metaphor of the wave versus the metaphor

of the “little body.” The battle of the wave versus the metaphor of the

cannonball, the billiard ball, and the bullet. The battle of the wave versus the

particle. Why? Because metaphor is the key to human understanding. And metaphor

is central to something that Aristotle invented: science.

But why?

We then get more background, in an attempt to answer this query, and

Bloom returns to another common tack, that of the classic two slit experiment,

wherein light seemingly ‘chooses’ to go through one slit or another. Of

course, the idea of choice is a metaphor, and Bloom is correct on this score,

and then he propounds this:

This is not easy to explain in words, so please hang in with

me. You now have two sheets of paper. One that’s got just one slit. Your light

concentrator. And one that has two slits in it. Your light separator. Now set

the candle and sheets up so that light from the candle goes through the one-slit

sheet and is concentrated, and so the light next goes through the two-slit

sheet. Yes, I know it’s confusing. But let the light from the two slits shine

on the wall. Turn off the lights. What will you get? Logically, you should get a

relatively normal wash of light on the wall. You often have two light sources,

two candles, two light bulbs overhead, or two lamps. And a normal wash of light

is the result. But a wash of light is not what you see on the wall. Not at all.

You see stripes. In fact, you see a lineup of stripes. Why?

Young said that the sideways ladder of stripes was due to the

same thing that made the water’s moiré—the water’s hatched and gridworked

plaid. In other words, Young declared that the stripes of light were made by the

same thing that rippled a liquid into a plaid. Said Young, the stripes of light

on your wall are due to interference. Where two peaks of light meet, they add to

each other. They make lines of brightness. Where two troughs meet, they

deepen each

other. They make lines of darkness. Hence light is not a particle. It is a wave.

A wave like the waves in water. Like the waves in Leonardo’s pond. Like the

waves in the ducks’ wake. And like the waves in Young’s ripple tank.

Now let’s step back and apply the second law of science for

a minute. Let’s look at things right under our noses—yours and mine—as if

we’ve never seen them before. Two swatches of light overlap and

make…darkness? This is an absurd notion. It makes absolutely no sense. How can

light added to light make light’s opposite, a swatch of black? How can one plus

one equal zero? That’s like saying two patches of night make day. But this

is not the only bit of absurdity at work in Young’s claim. It’s not the only

piece of outrageousness in Leonardo’s—and Young’s—idea that light is

like water. And it’s not the only bit of nonsense in Newton’s crazy idea

that light—the insubstantial stuff that you can run your hand through, the

immaterial flood you walk through every day—Newton’s crazy idea that light

is a rain of miniature bullets, billiard balls, or cannonballs. These ideas are

based on a stark-ravingly ridiculous platform, a lunatic assumption. They are

based on the idea that a pattern translates from one medium to another. And they

are based on the assumption that despite this violent displacement into soups,

goops, vacuums, and solids that seem to bear no relationship to each other, the

pattern will stubbornly maintain its identity. That assumption is the bottom

line of metaphor. And as Aristotle said, metaphor is unscientific. Right?

Why is metaphor so outrageous? So utterly unbelievable? Let

me repeat. In a rational world, light and water are violently different things.

There is no reason whatsoever that water and light should be the same. And in

truth, every laboratory demonstration, every chemical reaction in a test tube,

every act of genetic analysis in a sequencing machine, every experiment on

pigeons, rats, or pygmy chimps, every test of drugs on dogs or rabbits, and

every social science study based on sampling makes no sense. Every one of these

assumes that you can capture a pattern in one small patch of territory, in one

manifestation of nature, and blow it up big. What’s worse, every one of these

assumes that you can grab hold of a pattern in one kind of thing and generalize

it to radically different things. Every one of these assumes that you can take a

basic pattern and translate it the way Young translated the Rosetta Stone. That

you can translate it to something that is grotesquely different. And every one

of these carries another hidden assumption. That the real translator, the real

duplicator of a basic pattern in radically different mediums, is not you. The

hidden assumption is that the real translator is nature.

Several problems occur here: the first should be obvious, and that is

that, even as a laymen, I know that the Classical war over light, known as

wave-particle duality, states that light is not a particle nor wave, but acts

like a particle or wave, depending on how one views or measures it; but it

cannot act like both simultaneously. Now, forget about the lay difficulty in

understanding this materially, and concentrate on the fact that Bloom does not

recognize this in the excerpt, even as he previously acknowledged these were

metaphors. He seems to vacillate between the two, as if they were particles or

waves, not merely acting like they were, which is similar to the earlier

lack of recognition that a meme is merely a metaphor. Hence, he seems to have

gotten swept up in the very power of metaphor he is illustrating- again, a

recapitulative moment, which might seem almost a Postmodern tack, save for the

fact that he is speaking of an oft-repeated and confirmed and controlled

scientific experiment.

The larger issue is that while it is metaphoric to claim something

behaves in a certain way, the actual reduction of such A is like B claims

does not reduce it to metaphor but to simile, and simile is a more

precise comparison of things than metaphor, often using terms like as and

like. There is often some blurring of the boundaries between the two

things, but, generally, precise comparisons are similes, and metaphors are less

tangible things that use tangible elements to illustrate them. In short, similes

are more directly revealers of patterns, whereas metaphors are reductions,

enlargements, or sometimes projections that attack and stimulate similar modes

of thought re: patterns. Notice, even in describing them, I have used a metaphor

actively, that metaphors attack, to make my point. Metaphors can achieve

the same ends as similes, which rely on direct patterns, but if a simile can be

represented by having two different sized feathers tickling a naked foot’s

sole to try and induce laughter, then metaphor is akin to breaking someone’s

jaw, first by using a baseball bat, then by using brass knuckles. Like simile,

you’ve achieved a similar end, but you’ve used somewhat different means.

Now, you’ll note that this paragraph is a mixture of similes and metaphors, so

let me try again: similes use like means to achieve an end, whereas metaphors

are not so much about evincing patterns as getting similar ends or reactions to

those patterns. Bloom seems to not recognize this subtle, but important,

difference, and because it crops up several times in the book, I can imagine

that someone taking aim at his whole argument, as propounded in the book, might

very well see this mixup of metaphors and similes as the dangling thread from

Bloom’s sweater that unravels it all. As a critic, that is not my aim, but it

is my duty to report this, especially since it recurs.

Bloom sums up his

point this way:

But there is. Thomas Young proved it. Thomas Young proved

that a primal pattern, an ur pattern, repeats in two bizarrely separate mediums.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the essence of metaphor. Finding a pattern in

one medium and applying it to another. Finding a pattern in one context and

shifting it to another. Making an absurdly gargantuan leap.

But metaphor works. It works because it captures nature. It works because

it capture’s nature’s creativity. It works because of deep structures. Hell,

it works because there are deep structures. It works because of Ur

patterns. Is metaphor “unscientific.” Far from it. It is the very core of

science.

I agree with these two paragraphs, almost completely, and have long

thought that most scientists simply do not understand that their pursuits are

immersed in the larger human patterns and behaviors. It is similar to conundra

involving the observed and the observer, wherein the observer needs to recognize

observation is an active agent in a cosmos that includes himself; but, again,

that’s too long a digression for my purposes. However, as I’ve shown, the

wave-particle duality, and, indeed, much of what Bloom claims as metaphor, is

not, but simile. Is this merely semiotics? Should Bloom have stated and posited

his book on the idea that simile, not metaphor, is the core of science? I

don’t know. It’s not my field, and it’s not something that drives me to

pursuit, but, as with most artists who desire order, I loathe dangling threads,

and this seems to be one that is begging to be pulled by a rival or detractor,

and, unlike Bloom’s ideas’ reliance on the Big Bang- another thread that

could unravel portions of his posits, this one is entirely on Bloom.

Please defend your claim or counterattack my dissent.

HB:

That’s a good one because basically it’s this, when I 1st ran

across the differentiation between metaphor and simile—it goes back to

Aristotle. Aristotle in his Posterior Analytics, in 2 pages, mapped out the

entire program of science that we’ve been enacting for the past 2300 years,

and I won’t go into the details of what he mapped out, but what he said was

that metaphor is not science. So we inherited that prejudice from Aristotle, and

apparently in order to get around it, we came up with this distinction between

metaphor and simile. Well, I have to admit I don’t have the strongest mind in

the world, and there are some things that are utterly beyond me, and the

difference between metaphor and simile is one of those things that are utterly

beyond me, and to me, it looks like an artificial difference. It looks like

metaphor really is at the core of both of them, they are both different forms of

metaphor, assuming they’re different at all. And metaphor works because there

seem to be underlying patterns that show up at level after level in the cosmos.

For example, the best known underlying pattern is the Fibonacci Spiral and you

can find the Fibonacci Spiral everywhere

from the smallest of the micro-level to the biggest of the macro-level.

For example, in the 1990s, the big thing in technology was to try to get

superconductors to conduct electricity because it was said that superconductors

would be able to conduct electricity with no loss of power whatsoever. But there

was a problem. There was

a loss of power. Why? If you looked

at the microscopic level, the electrons didn’t want to travel in a straight

line—they wanted to do a little loop-de-loop.

In fact, they kept doing these little Fibonacci-like Spirals. So you have

spirals at the microscopic level and you have them at the macro-level whenever

you flush your toilet. What’s

more, you have them in the red spot on Jupiter, which is a giant Fibonacci

Spiral. It’s a tornado or hurricane weather system the size of 3 earths and it

has been there for over 350 years. And you have the spirals in the arms of

galaxies—the spiral arms. So there are certain underlying patterns that repeat

themselves at level after level of emergent property, and metaphor works because

it captures that underlying pattern at one level of emergence and then

generalizes it to many other forms of emergence. and when the metaphor is valid,

that generalization holds up. When it’s not a valid metaphor, and there are

lots that aren’t, it doesn’t hold up. For example, Kepler’s greatest

achievement he felt was figuring out how to use geometry’s five Platonic

solids to figure out the distance between the orbits of the planets. It was the

accomplishment he was the proudest of in his life. But guess what? It

didn’t fit the planets. It was a great metaphor but it didn’t work. So not

all metaphors work, but when they do, they succeed because they tap into what I

call in the book an Ur pattern, a primal pattern in the universe.

DS: In summing

up the book, I wrote:

In a sense, and because the book also functions as a de facto science

memoir, it offers up far more to say on the human mind than many other works in

a similar vein. In fact, despite my spending far more time on the book as a work

on cosmology and cosmogony, it may very well end up having far more to do with

how the human mind, and creativity work, for the very Ur patterns that Bloom

sees as fractal examples of nature gone outward could be interpreted, if one

accounts for Bloom’s belief in meaning, as merely projections of Ur patterns

in the human mind and brain. Of course, are these bits of residue from without,

or generated via instinct? And what is instinct? When does a pattern of thought

or behavior become instinct? What was, as example, the first human instinct? And

how did it form? These are corollaries to the very things this book raises, and

ties in to the books last claim: Sometimes new

questions are more important than new answers.

It’s notable that Bloom does not fall back on the cliché that art (or great

art or science) does not answer questions, it asks them, for great art and

science does answer those queries: one merely knows how to get them.

What do you think of my idea that, long term, The

God Problem may have more staying power as a work about the human

mind than the material cosmos?

HB:

Well, it’s an important question—think back to the story of your life.

You’re 10 years old and nobody wants you in your hometown, you discover these

two dead guys—Anton Van Leeuwenhoek and

Galileo. They cannot possibly not toss you out of their social group because

they’re dead, so they become your companions for the rest of your life. Now,

how long ago did they bump off this mortal coil? Roughly 300 years ago, so these

are two guys who reached out across a gap of three centuries to save your life.

So if these guys did that for you, it is your job to reach out over 300 years,

as pretentious as that possibly sounds, it’s your job to reach out over 300

years to that lonely kid 300 years from now who needs validation. And to show

him a path that will illuminate the rest of his life. So you’re stuck, you

have a mission. You have an

obligation. You have to write books that will outlast the centuries somehow. Are

the odds with you? No, the odds are 10 million to 1 against you at least, or

billions to 1 against you. Do you have to do it anyway? You sure as hell have

to, you owe it.

DS: Let me

briefly turn to your three earlier books, for readers unfamiliar with your

works. 1995 saw the release of The

Lucifer Principle: A Scientific Expedition Into The Forces Of History.

Another ominous title, and one which I first read and became familiar with

you. Please briefly give the readers a sense of the book, its theses, and

posits.

HB:

The Lucifer Principle—Peter Gabriel walked into my office one day and said

there’s this thing you’d be interested in by Lynn Margulis and James

Lovelock—it’s called the Gaia Hypothesis. So I looked into it, and I read an

article by Dorion Sagan and his mother Lynn Margulis who both became friends and

both became tremendous supporters of my work, and they talked about a mass die

off of bacteria during the oxygen crisis.

The Oxygen crisis is an event a few billion years ago in which a toxic

pollutant in the atmosphere, a pollutant the life forms of the day had been

merrily farting out, oxygen, started killing off all the life on earth. And the

enthusiasm with Sagan and Margulis wrote about this mass die off in nature

turned my stomach. It was great writing. But

the effervescent energy of the style was morally disturbing.

Remember, I grew up in the wake of WW2, in the shadow of the Holocaust,

and I was taught that your job is to stop a Holocaust. When you see a mass

murder of any kind or an injustice, your job is to stop it. So I decided to

write about the dark side of things. The

evil side. Why? To equip us

to stop the evil. So The Lucifer Principle is about the dark side of things and

about where evil comes from, even though we know that evil is relative.

One man’s evil is another man’s good, and basically The God Problem

says that it all boils down to the fact that human groups, whether they are

tribes or nations, are superorganisms in which individuals participate the way

that cells participate in the community of your body.

You think of your body as all one thing.

In fact, your body is 50 trillion cells communicating with each other.

And what pulls human superorganisms together, what pulls social groups together,

is often an idea. And ideas are these self-replicating things. It was Richard

Dawkins who came up with the term “meme” for ideas.

Dawkins also came up with the idea of replicators—things “greedy”

to make copies of themselves. One

replicator is the gene, a molecule selfishly grabbing biomaterials to make

copies of itself. Another is the meme, an idea greedy to grab mind stuff in

which it could multiply. And memes have this very powerful urge.

OK, it’s not an urge ‘cause memes are not conscious. But there’s a

powerful something, an impulse to procreate, to multiply themselves and when

groups go up against each other with different sets of ideas, that’s when one

man’s good becomes another man’s evil and that’s when the greatest evils

are performed. The irony is that

the greatest evils are often the greatest acts of selflessness. In other words a

suicide bomber in Afghanistan today gives up his life for a higher cause.

He sacrifices this earthly life to advance what he sees as the ultimate

truth. The truth of God.

He’s doing the ultimate act of heroism and goodness, isn’t he?

The problem is that he’s blowing himself up in a marketplace on a

holiday and killing large numbers of Afghan citizens—father, mothers, and

children. To your eyes and mine, there’s no way in hell he should be doing

that, but he’s doing it on behalf of an idea and it’s heroism, so one

man’s heroism is another’s murder.

One man’s selfless sacrifice is another’s evil.

Why? Because groups compete

to spread their ideas. And ideas

use groups to compete. That’s

basically The Lucifer Principle.

Then there’s Global Brain. We think it’s the Internet that’s

knitting us together in a Global Mind. But we’ve been a Global Mind since 3.85

billion years ago when life first began. Global

Brain shows you how bacteria live in colonies of 7 trillion and the individuals

in those colonies are all communicating all of the time and they have a

colony-level identity as well as an individual identity, and if they find a turd

that they love at the bottom of the ocean, 7 colonies will go to war over it and

they’ll use weapons of mass destruction—chemical weapons—against each

other. In fact, we’ve stolen bacteria’s chemical weapons., We call them

antibiotics because they kill off large masses of bacteria, but who do we get

them from? Microorganisms. But microorganisms, bacteria, communicate even when

they die, they wrap up their genome in a neat package and they send their

genetic fragments out as a warning not to go where they have gone.

Not to make the mistakes they have made. Healthy bacteria also swap gene

fragments, and these fragments are like how-to books on entirely new genetic

inventions, new gene-based techniques. Bacteria

swap these gene fragments between colonies.

And their gene fragments are

carried worldwide in the currents

of the sea. This worldwide communication system was at work 3.5 billion years

ago, so if we think it’s the Internet that started The Global Brain, we’ve

got to be kidding. That’s the essence of Global Brain.

Then there’s Genius of the Beast: A Radical Re-Vison of Capitalism.—I

started that book after 9/11 and after Enron and Worldcom fell apart, and we saw

all kinds of troubles in the Western Capitalism system. I wanted to focus you on

things we don’t normally realize about the Western system. If you’d been

born in 1850 in the Western system your life expectancy would have been 38.5

years. If you were born in the year 2000 in the Western system, your life

expectancy would have been 78.5 years. That’s

40 years more—more than twice the lifetime.

Two lifetimes for the price of one. That’s an amazement. No other

civilization has ever been able to pull that off, and believe me, the Chinese

wanted to pull it off millennium after millennium after millennium and they put

incredible amounts of resources into trying to achieve it and they never

did—ours did. If you were the lowest paid worker in London in 1850, you would

have earned a pittance, but if you’d been the lowest paid worker in England in

2007, you would have earned the equivalent of what 7 of the lowest paid

workers—they were Irish dock workers—pulled in in 1850. You would have

earned what an entire tenement of Irish doc workers earned 150 years earlier.

Every system of belief in the world has promised the same thing—raising the

poor and oppressed. But the only civilization, the only system, that has ever

done it is the Western system, and if we don’t recognize that, and if we

don’t carry those positives into the future and lengthen our kids and great

grandkids’ lifetime to 150 years and more, we aren’t doing our job. We are

failing in our obligation to the human race and to mother nature. So that’s

what the Genius of the Beast is about, but it’s about also about creativity,

the creativity of humans, surprising aspects of that creativity.

The new book is about the inherent creativity of the cosmos. But The

Genius of the Beast is about how human creativity happens and it’s an amazing

process with an amazing series of stories.

And The God Problem is about how the cosmos creates. And what holds all

these things together? What holds The Lucifer Principle, Global Brain, The Genius of

the Beast, and Global Brain together? An

urge to formfulness—in this universe, there’s an urge to overarching form,

there’s an urge to things coming together in

new big pictures and an urge to explode with new social aggregations that

have stunning new properties. And these 4 books are all about how that urge

works in the cosmos and in you and me.

DS: You also

belong to a group called Lifeboat, and wrote this

essay on their website, called Screw

Sustainability: The Age Of The Tornado Tamers Busting The Bubble Of Spaceship

Earth, wherein you write:

Why screw sustainability? Because the word implies merely hanging in

there, merely surviving, merely sustaining. It implies a penny-pinching earth, a

miserly existence, a nature that punishes change, and a nature that prefers

small tribes to large groups of human beings. This sort of attitude has

traditionally led to ignorance and to self-inflicted poverty. It pitched Europe

into misery from the fall of Rome in 476 AD to the revival of optimism,

technology, and entrepreneurialism in 1100 AD. That 600-year-long slump was the

famous dark ages of the West.

While I agree that some Left Wing extremists want to return to a

Golden Age that never existed, sustainability, in the sense that we do not

pillage the earth’s resources, is vital, and not fundamentally at odds with

growth. This seems to be a conflation that many people make. What is the point

of this essay?

HB:

About 6 years ago I was asked to give a speech at Yale University to a

conference on sustainability and I thought about it for a while. I couldn’t

believe they called me to do something on sustainability ‘cause I’m very

skeptical about the use of that word and I called the conference organizer and I

said I wanted to do a speech called Fuck Sustainability.

I thought he’d hang up the phone.

But he fell off his seat laughing—the basic idea is this—organisms,

whether they’re bacteria, mice or human beings-- go through 2 different

phases—when they think they’re at the

beginning of a whole new frontier of possibilities and resources they go into a

new mode, they are exuberant and lusty—they eat, drink and be merry, they

absorb resources like crazy, they come up with all kinds of new ideas on how to

use the resources and new emergent

properties start spinning forth. But there’s another phase that every life

form goes through, when it thinks it’s reached the carrying capacity in its

environment, it goes through a phase of physiologically based self-denial. And

it denies itself food, space, it denies itself sexuality and exuberance. We see

this in social animals like mice, voles, and lemmings. And we saw it in 500 AD

when the Roman Empire fell and we went through 600 bloody years of this form of

self-denial in the Dark Ages, and I don’t want to see it again. And

eco-thinking, which began to popularize itself with tremendous success in the

1960s, had a point—you don’t want to poison the air you breathe, you don’t

want to poison the water or kill all the other creatures and species on the face

of this earth—they hold genetic diversity. You have to have a balance and

maintain nature. But then there are some in Scandinavia, the deep greens, the

deep ecologists, and they say there is room for only 100 million people on this

planet because this is a planet of animals and plants and we don’t really

belong here. Well, screw them, Dan. Absolutely screw them. They’re dead wrong.

They have a genocidal philosophy—they want 6 billion people to die. One of

them, Pentti Linkola, says when those folks are drowning and reach out their

hands from the waters to grab the rim of the lifeboat, it is our job to chop

those hands off with an axe. This is not kindly. This is not the pluralism,

tolerance, freedom of speech and exuberance that you or I believe in. So the

eco-thinking has gone too far and it has convinced us that we have raped and

plundered the planet’s resources—that is bullshit. For every ounce of

biomass on this planet, there are 220 million ounces of resources, 220 million

ounces of other stuff, just waiting to be turned into biomass. Biomass has

barely begun to scratch the surface of the earth. Literally. And if we don’t

know that our obligation is to spread biomass and to spread life and to spread

it beyond this planet to not only other heavenly bodies—moons, planets, solar

systems, but to habitations that we can make that spin in space and create

artificial gravity and just hang in the sun and suck up the sunlight--if we

don’t know that’s our obligation, we are failing the life process.

DS: How did

you get involved with Lifeboat?

What are its pros and cons?

HB:

I really have never been able to figure out the group, I became a member of

their Scientific Advisory Board because I respect the people involved. Eric

Klein is a terrific social collector and he’s the one who runs the group and I

was asked by Amara Angelica, who runs Ray Kurzweil’s website, KurzweilAI.

Amara is one of the smartest and best

people that I know on the planet, she is way ahead of the curve on every

existing technology you’ve ever heard of and she’s a former aerospace

scientist and a former publicist who worked with Bill Gates and I think worked

with Steve Jobs at one point, but one way or the other she’s a stunning

person, in terms of her mind, so if she asks me to be on the Scientific Advisory

Board of a group and she believes in it powerfully then I will do it. So I’m

there to give advice if they need it.

DS: As you are

a man in both the arts and sciences, I’ve always felt that art is a greater

human pursuit than science for the great artist is always one of a kind, whereas

the great scientist is merely a discoverer of things that are essentially

inevitable. Remove Darwin and there’s Wallace. Remove Marconi or Edison and

there’s Tesla. But there are no replacements for Whitman, Melville, or Monet.

In other words, remove Whitman and Melville, and two of the most influential

English language books of the 1850s are gone, Leaves

Of Grass and Moby-Dick,

and their two arts, poetry and prose, take different course. But, remove

Darwin and almost all stays the same, On

The Origin Of Species, or not. Agree or not?

HB:

There is a mission I wanted to carry out in this book but wasn’t able to

because I had to bring it in at a reasonable length.

It’s already twice as long as what my publisher wanted.

Let’s go back to James Burke, who says it’s the most amazing thriller

that he can remember reading. Well that’s great. So some people love going

through a 600 page book. But I wanted to talk about why science and art are

joined at the hip, ‘cause Dan, I also do visual arts. My way of sneaking into

the pop culture business in 1968 was to found an art studio that became one of

the leading avant-guard commercial arts studios on the East Coast in the late

1960s and early 1970s. I love art and I love poetry—I edited and art-directed

a poetry and experimental graphics magazine that won 2 National Academy of Poets

prizes, for God’s sakes. And my

photography has been shown at Art Basel in Florida, the most highly competitive

art festival in North America, a festival that artists kill and die to get into.

This stuff is important to me. But why? Both these things, art and

science, try to grasp the mysteries of the universe using some form of

metaphoric expression. Some form of symbolic expression. And if you’ve

got a mystery and can only grasp it through poetry or you can only grasp

it through the visual arts, then grasp it for God’s sakes, because the job of

humanity is to step out into the unknown of the darkness and bring a bit of

light, and then once we can see what’s in shadow, we can ponder it with the

sciences. Science and art are joined at the hip. They’re part of the same

process—learning to perceive things in whole new ways and learning to predict

their properties, their emergent properties.

Why? So we can help develop

new emergent properties. Again,

why? Because we are engines of

cosmic creativity. So is everything that has ever been spun in this world. Atoms

were engines of cosmic creativity, stars and galaxies and life forms were

engines of cosmic creativity. Absolutely.

All of us are here to produce more creativity.

But humans have more than stars, galaxies, bacteria, plants, and our

fellow animals have ever been given. We

have a consciousness, imagination, art and sciences. The wonders of what we can

accomplish can go beyond any kind of wonders that the cosmos has produced

before. If we live up to our destiny and our possibilities.

If we live up to what nature demands of us.

DS: Let us now

get into who you are and where you’ve been. Let us start from the beginning,

with some biographical plumbing of your past, your career, your views on science

and religion, etc. When and where were you born?

HB:

I was born in Buffalo, NY on June 25, 1943.

DS: What was

your youth like, both at home and in terms of socializing with other children?

Were you drawn to the outdoors, or were you more of a geek with a book at all

times?

HB:

My youth was miserable, I was born during WW2, my dad was off in the Navy in San

Francisco, and only came home to visit once.

When he was drafted, my dad had just started a tiny liquor store. So my mom had to work the store. We didn’t have au pairs in

those days, and , for some reason, my mom didn’t hire babysitters, she hired

cleaning ladies, so they thought their job was to hug the vacuum cleaner very

close to their chests and to listen to soap operas on the radio and they locked

me in a dark corridor. and so I grew up in a dark corridor crawling around on a

hard, cold wood floor and kept away from the sunlight and from human company.

So it wasn’t a pleasant childhood, and so then when I became associated

with other kids, if you raise an infant monkey in isolation it doesn’t have

the right instincts to hang out with the gang. It just doesn’t know how to

handle sociality. So when I started meeting other kids at the age of 3 and a

half they didn’t want anything to do with me and that kept up till I was 10

except once upon a time when I was eight, the

group of kids who had tortured me for years took me over to the Jewish

Center and elected me as president of the stamp club—so I became accepted as

head of things, but not accepted as a member of anything and it wasn’t until

Galileo and van Leeuwenhoek that I had a social group in which I could fit, and

a system of belief that I could hug to my heart.

That system of belief was the 1st 2 rules of science and that

social group was the scientific community. And then along came Einstein and

validated my right to exist. I was the most

absent-minded kid on the planet. In my book, I put you in my place. I make you

go to my dining room and to look for the scissors, which is always kept in the

same drawer in exactly the same place and you can’t find it, it isn’t there,

and you go through every single room of your three-story Tudor house and you

can’t find them. Then you go back to the dining room and stare at that damned

drawer, hoping that if you stare hard enough the scissors will reappear where it

usually is. Then you finally

notice where the scissors is. It’s in your left hand and it’s been there all

along and you realize you need someone to validate you for being so ridiculously

absent-minded, and Albert Einstein writes an autobiography and you read it at 11

years old, and Einstein tells you that he is so absent-minded that he walks out

of his house in Princeton every day and gets 2 blocks up towards the Institute

for Advanced Study and his wife comes running up the street behind him with her

arms full saying, Albert you forgot something. And what are her arms full of?

Einstein’s pants, his shirt, and his shoes. Einstein has forgotten to

take off his pajamas and his bedroom slippers and get dressed before going up to

the Institute for Advanced Studies. And that story gives you a right to be. So I’ve spent my life

in science and one of the reasons I felt I had permission to go off into popular

culture for 20 years and work with Michael Jackson, Prince, Billy Joel and Billy

Idol was because I’d spent so much of my life in science at that point that it

was just a part of my bones, a part of my marrow, and it would never leave me,

so I was able to go into a quest into pop culture without ever leaving my

science behind.

DS:

How did you first get into rock and roll? Were you a failed Rock God- a Jeff

Beck or Donovan wannabe, and did the next best thing? How did you segue from

rock management into Public Relations? Some of the bigger name stars you dealt

with were Prince, Michael Jackson, AC/DC, Simon & Garfunkel, Billy Joel,

Styx, Run DMC, Kiss, and Bob Marley. From what is available, it seems your task

was usually in how to expand these performers from stars in a specific field

into mainstream acts. What were some of the techniques used, and what was your

greatest success? Your least successful ‘project’?

HB:

I got into Rock and Roll because I was sort of kidnapped by the Poet in

Residence at NYU. One day, he made

me stay after class and he said last year I asked you to be on the staff of the

literary magazine and you never showed up.

This year I’m telling you something.

The minute you walk out of this door, you are the editor of the literary

magazine. You are the literary magazine. You have no outs, you don’t

even have a faculty advisor, it’s you. And so I turned the literary magazine

into an experimental graphics magazine and it won three National Academy of

Poets prizes and I started getting requests for meetings from the art directors

of major national magazines. Look

Magazine, which was huge and glossy, Boy’s Life, which is a magazine I grew up

on because I was a member of the Boy Scouts until they threw me out for

incompetence at Morse Code, and Evergreen Review [?], which was the

leading bohemian magazine of the

day. Meanwhile, I had been married

since I was a freshman in college and my wife said she

couldn’t stand having student husbands anymore and I had 4 grad school

fellowships and I realized I was on the track of what Hitler used to rouse mass

attention—that artistry of mass emotions that gives people the feeling of

being exhilarated and part of something bigger than themselves-- and that I was

not going to find that in grad school.

Entering the ivory tower of academia was going to be like Auschwitz for

the mind.

So I jumped ship and went with the artists I had accumulated to staff the

magazine and started an art studio and regarded it as a periscope position to

find my way into something I didn’t know anything about—pop culture.

What’s more, Einstein had said something in one of his intros to his

books that was very important to me when I was 12. He said, look, schmuck, you

want to be a genius and an original scientific thinker? Then it’s not enough

to be able to come up with a theory that only 3 men in the world can understand.

You have to be able to come up with a theory that only 3 men in the world can

understand and you have to be able to express it so vividly that anyone with a

high school education and a reasonable degree of intelligence can understand it.

So Einstein said if you really want to be a scientist like me, you have to be a

writer. So when I was asked to edit a magazine in 1971, I said yes, I didn’t

ask what it was about and my artists didn’t need me anymore, and when I walked

into the meeting with the publisher, it

turned out it was a magazine about rock and roll, which I knew nothing about,

but at that point I had been writing professionally since 1963, when I was

twenty. I figured I could write about anything, if I cared about the audience

and could dive into research, so I doubled the circulation of the magazine—Circus--and

I was credited with founding a

whole new magazine genre by Chet Flippo, one of the founding editors of Rolling

Stone. Chet wrote a master’s thesis on the history of rock journalism and said

I had founded this new genre called The Heavy Metal Magazine.

Then I was hired to form a public and artist relations department for

Gulf & Western’s 14 record companies. And one day, my mentor in the music

industry, Seymour Stein, the president of Sire Records and the man who

eventually signed Madonna, walked into my office.

Seymour had been remarkably kind to me, and he and his wife would take me

and my wife out to dinner and they’d take us to parts of Brooklyn I’d never

seen before in my life. They’d have us meet them at their apartment overlooking

Central Park in a building where Paul Simon lived and I’d look through the

original paintings by classic Art Nouveau masters like Mucha stacked against the

wall while Seymour had long phone conversations with Elton John in England about what art nouveau masterpiece to buy

next. So Seymour walked into my

office one day and said schmuck, if you’re so smart, why don’t you have your

own company. So eventually I founded my own company in the rock and roll

publicity business. I had no

training in publicity, but I’d been receiving phone calls as a magazine editor

from publicists for two years, and I could see what they were doing that worked

and I could see what they were doing that didn’t. And I founded my own company

and designed it to give a level of service that had never existed in the music

industry before. My greatest

success successes were Prince, Billy Idol, John Mellencamp and Joan Jett. In

Joan Jett’s case, she’d been turned down by 23 record companies—no record

company wanted to have anything to do with her.

I believed in her and I loved her manager, who was a song writer who had

always been extremely warm to me. So